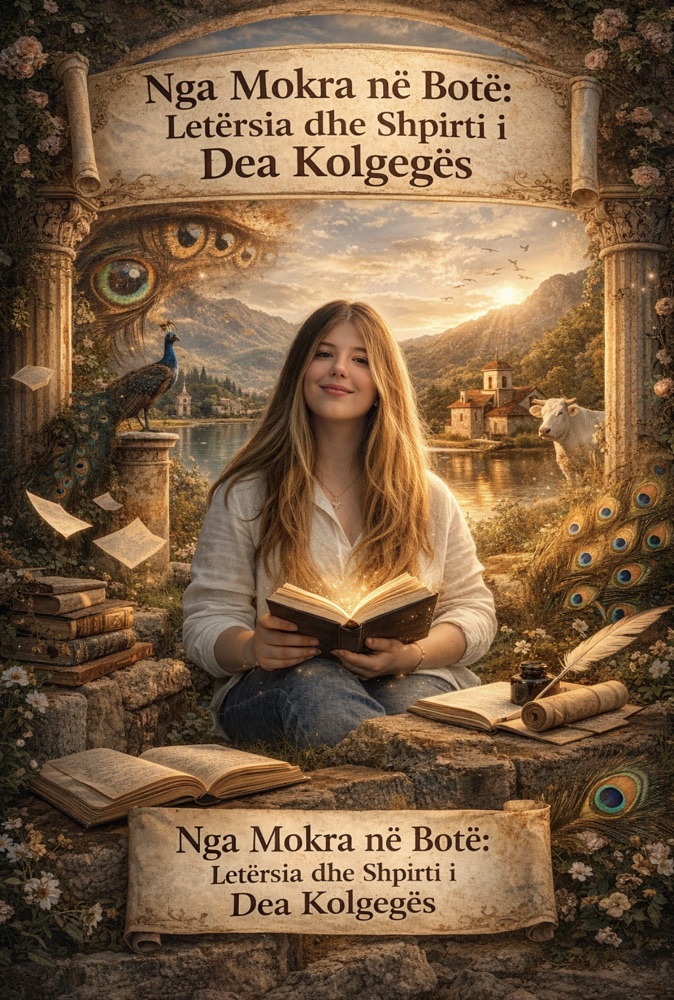

Dea Kolgega është një zë i ri dhe i fuqishëm në botën e letërsisë, një autore që kombinon pasionin, kuriozitetin dhe ndjeshmërinë për të kapur thelbin e natyrës njerëzore.

E lindur dhe rritur në Shtetet e Bashkuara, por me rrënjë të thella në Mokër, Dea ka zhvilluar një aftësi të jashtëzakonshme për të depërtuar në psikologjinë e personazheve dhe kuptimet e fshehura të tregimeve që lexon dhe analizon.

Që nga fëmijëria, leximi dhe shkrimi kanë qenë për të më shumë se një hobi; ato janë një pasqyrë e botës dhe një mënyrë për të kuptuar veten dhe të tjerët, një udhëtim drejt reflektimit dhe njohjes së vetes.

Në analizën e saj të The Giver nga Lois Lowry, Dea tregon një perceptim të rrallë për izolimin, barrën e kujtimeve dhe përgjegjësinë ndaj një komuniteti që nuk e kupton protagonistin. Eseja e saj thekson se jeta e Jonas nuk është thjesht një përvojë fikse, por një lloj ndëshkimi psikologjik dhe emocional, duke e detyruar atë të përballet me izolimin dhe barrën e njohurive që askush tjetër nuk mund ta ndajë.

Ajo shpjegon se Lowry përdor një botë të rregulluar, ku emocionet dhe zgjedhjet janë të ndaluara, për të eksploruar lirinë, zgjedhjen dhe thelbin e përvojës njerëzore. Nëpërmjet kësaj eseje, Dea depërton në mendjet e personazheve dhe na lejon të ndjejmë çdo tension, çdo përgjegjësi dhe çdo dilemë morale që përjeton Jonas.

Lexuesi nuk merr vetëm një histori; ai përjeton dramat e brendshme, tensionin emocional dhe kompleksitetin moral që përbën një jetë të ndërtuar mbi zgjedhjet dhe ndjesitë e ndaluara. Ky recension tregon një sens të jashtëzakonshëm intelektual dhe emocional: Dea nuk ndalet tek përshkrimi i ngjarjeve, por depërton në psikologjinë e personazheve dhe mesazhet më të thella që letërsia përpiqet të komunikojë.

Në interpretimin e saj të mitit të Ovidit, Argus dhe Io, Dea shfaq një sens të thellë për transformimin e dhimbjes në kuptim dhe bukuri. Syte e Argusit, të cilët më pas shndërrohen në bishtin e paukut, bëhen simbol i reziliencës, ruajtjes së identitetit dhe aftësisë për të kthyer vuajtjen në art.

Ajo thekson se Ovidi përdor metamorfizmin si një mënyrë për të ruajtur identitetin dhe për të kthyer dhimbjen në diçka të bukur dhe të kuptueshme. Përmes këtij miti, Dea lidh dhimbjen, transformimin dhe rimëkëmbjen me psikologjinë moderne, fuqinë e resiliencës dhe aftësinë e njeriut për të nxjerrë kuptim nga përvoja më e dhimbshme.

Eseja e saj tregon se letërsia nuk është thjesht një tregim; ajo është një udhë për të kuptuar veten, emocionet dhe botën që na rrethon, një mënyrë për të reflektuar mbi jetën dhe marrëdhëniet njerëzore.

Recensionet dhe analizat e Deas nuk janë thjesht akademike. Ato janë një udhëtim emocional dhe intelektual, një eksplorim i thellë i përvojës njerëzore dhe i kompleksitetit të emocioneve që përbëjnë jetën.

Lexuesi ndjen dramën, bukurinë dhe kompleksitetin moral të tregimeve, duke u përfshirë në reflektimin mbi lirinë, dhimbjen dhe fuqinë e resiliencës. Ajo nuk ndalet tek ngjarjet, por depërton në psikologjinë e personazheve, motivet e tyre dhe mesazhet më të thella të letërsisë. Çdo tekst i saj është një përvojë personale, një hap drejt të kuptuarit më të plotë të botës dhe njerëzve që e banojnë. Ky kombinim i intelectit, empatisë dhe talentit letrar e bën çdo ese të saj një përvojë personale dhe transformuese.

Rrënjët e saj nga Mokra dhe trashëgimia intelektuale e familjes krijojnë një profil të veçantë dhe të fuqishëm: një autore që ndriçon faqen e letërsisë me pasion, reflektim dhe kulturë.

Gjyshi i saj Xhevairi ishte një kuadër, drejtues i respektuar i kooperativës bujqësore në Mokër, duke ndryshuar historinë dhe zhvillimin e asaj krahine përmes punës së tij të palodhur, ndërsa gjysja e saj, mësuesja Elvira Berberi Kolgega, ishte një thesar i arsimit në krahinën e tyre e ka mësuar në hapat e saj të para të edukimit dhe të arsimimit në USA .

Ky kombinim i rrënjëve të forta dhe edukimit modern ka krijuar një frymë intelektuale dhe humane te Dea, duke e bërë atë jo vetëm një autore, por edhe një frymëzuese, një interpretuese e ndjeshme e jetës dhe një zë i jashtëzakonshëm në letërsinë bashkëkohore.

Trashëgimia e saj tregon një lidhje të veçantë midis traditës dhe modernitetit, midis familjes dhe botës, duke e bërë Dean një figurë unike që i bashkon rrënjët shqiptare me botën globale.

Ajo nuk është vetëm një autore; ajo është një rrëfimtar i jashtëzakonshëm, një interpretuese e ndjeshme e jetës dhe një dritë që ndriçon rrugën për lexuesit e së ardhmes.

Eseja dhe recensionet e saj tregojnë se nga Mokra në botë, Dea Kolgega po lë gjurmë të paharrueshme në letërsinë bashkëkohore, duke bërë çdo lexim një udhëtim transformues, emocional dhe intelektual që nuk harrohet lehtë.

Çdo rresht i saj është një përvojë që bashkon dijen, ndjeshmërinë dhe pasionin, duke e bërë Dean një prej zërave më premtues dhe më frymëzues të kohës sonë.

Në një botë ku zërat e rinj shpesh humbasin në kaosin e informacionit dhe mediave të shpejta, Dea Kolgega shkëlqen si një menduese e thellë dhe një autore që sjell bukurinë, mendimin dhe emocionin në çdo rresht që shkruan.

Ajo kap lexuesin nga fillimi me njohuritë dhe talentin e saj analitik, por e mban me ndjeshmërinë dhe pasionin e saj, duke e bërë leximin një përvojë jo vetëm intelektuale, por edhe shpirtërore.

Letërsia e Deas është një udhëtim në të brendshmen e njeriut, një reflektim mbi dhimbjen, transformimin dhe fuqinë e shpresës, dhe një dëshmi e qartë se një zë i ri me rrënjë të forta mund të ndryshojë mënyrën se si lexuesit e gjithë botës e përjetojnë letërsinë.

The Giver - Lois Lowry Anglisht:

Punishment comes in a plethora of different forms: purely physical, mental, emotional or a mix of all three. In contrast, not all punishments given are deserved. The novel The Giver by Lois Lowry is an example of just such a situation. It is the story of Jonas and his struggle to do right by his community. Jonas lives in a perfect world. Nobody is unhappy, and everyone enjoys their lives. As children turn twelve, they find out what job they will have as adults. Jonas is given a job that no one in the community really understands, except that it is position of great honor. The book gets at the major concepts of choice and emotions by describing a world where neither exist. Jonas’s assignment as the next Receiver of Memory is a punishment because he cannot share the burden of memory with anyone and he is isolated from others.

For such a young, naive soul like Jonas, his accustomed life has now broken to pieces. The worst part is, he can’t even share the horrible burden and “concept” of memory to anyone. After the Ceremony of Twelves (A ceremony held to assign all of the Twelves a career, better known as ‘Assignment’.) Jonas was given a sheet of rules that precisely stated he was not allowed to talk about the training and preparation he endures with anyone except for the Giver. The Giver is the previous Receiver of Memory, whom of which is now instructing Jonas on how to be one himself. Being restricted from talking about what he and the Giver know to others really places a lot of nervous tension and pressure on Jonas. It is too much for the average person let alone an inexperienced teen like Jonas, who is just now figuring out the rights and wrongs of his Assignment. Not only that, but he can also now no longer participate in things that he has grown up doing; things like dream telling, feeling, and sharing his emotions. In Jonas’s family Unit it was required that each night one would have to share about how they’re feeling at dinner, and express the events of their dream in the morning at breakfast. In the present day, he knows that now these can not be followed; his knowledge forces him to lie in the situations he is inevitably expected to participate in. Recalling the rules, they state he “may” lie, but in many circumstances like this, it should say he “must” lie. For Jonas, this is a very big deal because he was always seen as a “perfect child” and he rarely had many flaws. His Assignment has taken away the privilege for him to mentally and physically feel like a normal kid. Not to mention, but his ‘rose colored glasses’ aren’t apparent anymore. He sees that rituals and certain rules are a manipulative tool to control the civilians in his Community. Quite obviously, no one knows about this except for Jonas. Not being able to take action or do something about this rubs Jonas the wrong way. While he can break the rules, he will still have to face detrimental consequences. This brings onto how he is aware of what will happen to the Community if he shares his memories.

Around a decade ago, there was different Receiver of Memory in training. Her name was Rosemary. After experiencing the bright happiness along with the horrible agony of certain memories, she went straight to be Released. She didn't want the memories. They got into her head and she couldn't take it anymore. No where in the rules at that time did state that she wasn’t allowed to be Released. With this being a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, the community was shocked to discover that the memories Rosemary held didn’t disintegrate into thin air, they dispersed throughout everyone within the Community. This rose chaos and it took a very long time for the memories to be assimilated into the Community; the people didn't want these memories. As Rosemary may not have known about the consequences of her actions, Jonas comprehends the fact that if he desperately wants to be Released as well, he cant.

The reason for this is that not only is it now written in the rules, but he also is able to grasp the idea that it will negatively affect people and he will have to face the guilt of bringing the intense, painful feelings as well as happy ones to the Community. This is why he comes up with the idea of running away. If he can’t be released, then running away and disappearing would be the second resort. He talks this over with the Giver. As this happens, Jonas begs the Giver to come with him. In Lowry’s The Giver, she states,

‘I want to, Jonas. If I go with you, and together we take away all their protection from the memories, Jonas, the community will be left with no one to help them. They’ll be thrown into chaos. They’ll destroy themselves. I can’t go.’

‘Giver,’ Jonas suggested, ‘you and I don’t need to care about the rest of them.’ The Giver looked at him with a questioning smile. Jonas hung his head. Of course they needed to care. It was the meaning of everything. (133)

Here, Jonas’s understanding of why the Giver must stay is very clear to him. The goal is for the community to fully live the human experience, but Jonas knows this will bring them pain, and he feels bad about the fact that he wants the Giver to come with him. Facing this guilt of selfishness is part of the punishment of his Assignment.

At the same time, when thinking of one of the worst things to experience in life, isolation might be something that comes to mind straight away. Jonas suffers this experience throughout the book. He is isolated and lonely. Physically and mentally, Jonas is being placed above everyone else in the Community. Throughout his whole life, Jonas has always been different from the others. He continuously stood out because he was the only one who had light-colored eyes. In theory, light eyes are widely known to show more of a story than darker eyes. At the Ceremony of Twelves, Jonas was initially skipped when the selection began, causing him to think this was just a slight mistake. Small panic arose, as the Elders are never prohibited to make a mistake, but many brushed it off as such, too afraid to actually ask about it. However he was skipped for a reason, the reason being that after everyone else got their selection, he would be called up onto the podium to be told he was to now and forever be honored. The Elder had stated that Jonas was a special person, he had the “capacity to see beyond.” Getting called this by the Elder also makes him secluded from the rest. This started some sort of unspoken but recognized hierarchy in the Community.

One moment Jonas was one amongst hundreds of Twelves awaiting to be assigned a position, and the next moment Jonas was a respected and distinguishable person. Jonas wasn’t fond of the fact that he now had to be recognized, as being acknowledged meant that he stuck out, thus proving the point of how he is in complete isolation when it comes to being the Receiver of Memory. The only person he can really express and talk to in this circumstance, is the Giver. In addition, Jonas’s community also has no concept of the idea of color, pain and animals. This is very insignificant to them, not one soul in the entire Community is able to perceive the idea of any of these topics. This makes him feel as if it is unfair to both him and the citizens in his community. Everyone lacks the capability he has and in under those circumstances is why his job as Receiver of Memory is a punishment.

In The Giver, Lowry exclaims, “He placed one hand on each of their shoulders. With all of his being he tried to give each of them a piece of the memory: not of the tortured cry of the elephant, but of the being of the elephant” (101). Here, Lowry demonstrates Jonas’s feeling of isolation very significantly. Jonas’s father is completely ignorant of what he is doing, and his sister is bothered by the fact that he’s touching her. She does not want this physical connection between her and Jonas. When Jonas tells her about the past existence of elephants, she thinks he’s kidding and just plays it off by not believing him. This puts Jonas in a tough position because expressing feelings to family is something many people do to exhale all of the bad energy, and lift a huge weight off of their back. However, without having shared experiences with anyone other than the Giver, Jonas is left all by himself to deal with all of the detrimental and beneficial outcomes of knowledge.

When one considers that the protagonist is excluded by his community and that he must carry and hold all of the memories and emotions it is clear that his position is one that makes him sacrifice to their way of life. Lowry wants the reader to consider what happens when people refuse to acknowledge that there is room for multiple possibilities within a society. This refusal to see that there is more than one choice in any given situation stagnates their growth. Taking away the freedom of choice in the name of safety is never a good way to live. After all, as Professor Dumbeldore explains to Harry in The Chamber of Secrets, “It is our choices, Harry, that we show what we truly are, far more than our abilities."

The Giver - Lois Lowry Shqipe:

Ndëshkimi vjen në një bollëk të formave të ndryshme: thjesht fizike, mendore, emocionale ose një përzierje e të treve. Në të kundërt, jo të gjitha dënimet e dhëna janë të merituara. Romani Dhënësi nga Lois Lowry është një shembull i një situate të tillë. Isshtë historia e Jonas dhe luftës së tij për të bërë mirë nga komuniteti i tij. Jonas jeton në një botë të përsosur. Askush nuk është i pakënaqur, dhe të gjithë gëzojnë jetën e tyre. Ndërsa fëmijët mbushin dymbëdhjetë vjeç, ata zbulojnë se çfarë pune do të kenë si të rritur. Jonas i është dhënë një punë që askush në komunitet nuk e kupton me të vërtetë, përveç se është një pozitë me shumë nder. Libri merr konceptet kryesore të zgjedhjes dhe emocioneve duke përshkruar një botë ku asnjëra nuk ekziston. Caktimi i Jonas si Marrësi tjetër i Kujtesës është një dënim sepse ai nuk mund ta ndajë barrën e kujtesës me askënd dhe ai është i izoluar nga të tjerët.

Për një shpirt kaq të ri, naiv si Jonas, jeta e tij e mësuar tani është bërë copë-copë. Pjesa më e keqe është, ai madje nuk mund të ndajë askënd barrën e tmerrshme dhe "konceptin" e kujtesës. Pas Ceremonisë së Të Dyshëve (Një ceremoni e mbajtur për të caktuar të gjithë Të Dyve një karrierë, e njohur më mirë si 'Caktimi'.) Jonas iu dha një fletë rregullash që saktësisht thoshte se nuk ishte i lejuar të fliste për trajnimin dhe përgatitjen me të cilën duron ndokush përveç Dhuruesit. Dhuruesi është Marrësi i mëparshëm i Kujtesës, nga të cilët tani po udhëzohet Jonas se si të jetë vetë ai. Duke qenë i kufizuar të flasësh për ato që ai dhe Dhuruesi i dinë të tjerëve, në të vërtetë krijon shumë tension nervor dhe presion mbi Jonas. Tooshtë shumë për një person mesatar e lëre më për një adoleshent të papërvojë si Jonas, i cili vetëm tani po kupton të drejtat dhe gabimet e Caktimit të tij. Jo vetëm kaq, por ai gjithashtu tani nuk mund të marrë më pjesë në gjëra që ai është rritur duke bërë; gjëra të tilla si tregimi i ëndrrave, ndjenjat dhe ndarja e emocioneve të tij. Në Njësinë e familjes së Jonas kërkohej që secila natë të duhej të ndanin se si po ndihen në darkë dhe të shprehin ngjarjet e ëndrrës së tyre në mëngjes në mëngjes. Në ditët e sotme, ai e di se tani këto nuk mund të ndiqen; njohuritë e tij e detyrojnë atë të shtrihet në situatat në të cilat pritet të marrë pjesë në mënyrë të pashmangshme. Duke kujtuar rregullat, ata deklarojnë se ai "mund" të gënjejë, por në shumë rrethana si kjo, duhet të thotë se ai "duhet" të gënjejë. Për Jonas, kjo është një punë shumë e madhe sepse ai gjithmonë shihej si një "fëmijë i përsosur" dhe ai rrallë kishte shumë të meta. Caktimi i tij i ka hequr privilegjin që ai të ndihet mendërisht dhe fizikisht si një fëmijë normal. Për të mos përmendur, por syzet e tij me ngjyrë trëndafili nuk janë më të dukshme. Ai e sheh që ritualet dhe rregullat e caktuara janë një mjet manipulues për të kontrolluar civilët në Komunitetin e tij. Padyshim, askush nuk e di për këtë përveç Jonas. Të mos jesh në gjendje të ndërmarrësh veprime ose të bësh diçka në lidhje me këtë e fërkon Jonas në mënyrën e gabuar. Ndërsa ai mund të thyejë rregullat, ai do të duhet ende të përballet me pasoja të dëmshme. Kjo sjell sesi ai është i vetëdijshëm për atë që do të ndodhë me Komunitetin nëse ndan kujtimet e tij. Rreth një dekadë më parë, kishte një Marrës të ndryshëm të Kujtesës në trajnim. Emri i saj ishte Rosemary. Pasi përjetoi lumturinë e ndritshme së bashku me agoninë e tmerrshme të kujtimeve të caktuara, ajo shkoi drejt e për t'u Liruar. Ajo nuk i donte kujtimet. Ata iu futën në kokë dhe ajo nuk mund të duronte më. Jo, ku në rregullat e asaj kohe thuhej se ajo nuk u lejua të lirohej. Meqë kjo ishte një dukuri një herë në jetë, komuniteti u trondit kur zbuloi se kujtimet që mbajti Rosemary nuk u shpërbëhen në ajër, ato u shpërndanë në të gjithë brenda Komunitetit. Ky kaos u ngrit dhe u desh një kohë shumë e gjatë që kujtimet të asimiloheshin në Komunitet; njerëzit nuk i donin këto kujtime. Meqenëse Rosemary mund të mos ketë ditur për pasojat e veprimeve të saj, Jonas kupton faktin se nëse dëshiron shumë të lirohet gjithashtu, ai nuk mundet. Arsyeja për këtë është se jo vetëm që është shkruar tani në rregulla, por ai gjithashtu është në gjendje të kuptojë idenë se kjo do të ndikojë negativisht tek njerëzit dhe ai do të duhet të përballet me fajin e sjelljes së ndjenjave të forta, të dhimbshme, si dhe të lumtur ato në Komunitet. Kjo është arsyeja pse ai vjen me idenë për të ikur. Nëse ai nuk mund të lirohet, atëherë ikja dhe zhdukja do të ishte zgjidhja e dytë. Ai e flet këtë me Dhuruesin. Ndërsa kjo ndodh, Jonas i lutet Dhënësit që të vijë me të. Në Lowry’s The Diver, ajo thotë,

‘Dua, Jonas. Nëse unë shkoj me ty dhe së bashku ne u heqim të gjitha mbrojtjet nga kujtimet, Jonas, komuniteti nuk do të mbetet askush për t'i ndihmuar. Ata do të hidhen në kaos. Ata do të shkatërrojnë veten e tyre. Unë nuk mund të shkoj. ’

‘Dhurues,’ sugjeroi Jonas, ‘ti dhe unë nuk kemi nevojë të kujdesemi për pjesën tjetër të tyre.’ Dhënësi e shikoi atë me një buzëqeshje pyetëse. Jonas vari kokën. Sigurisht që ata kishin nevojë të kujdeseshin. Ishte kuptimi i gjithçkaje. (133)

Këtu, kuptimi i Jonas se pse Dhuruesi duhet të qëndrojë është shumë i qartë për të. Qëllimi është që komuniteti të jetojë plotësisht përvojën njerëzore, por Jonas e di që kjo do t'u sjellë atyre dhimbje, dhe ai ndihet keq për faktin se ai dëshiron që Dhënësi të vijë me të. Përballja me këtë faj të egoizmit është pjesë e ndëshkimit të Caktimit të tij. Në të njëjtën kohë, kur mendon për një nga gjërat më të këqija për të përjetuar në jetë, izolimi mund të jetë diçka që të vjen ndërmend menjëherë. Jonas e vuan këtë përvojë gjatë gjithë librit. Ai është i izoluar dhe i vetmuar. Fizikisht dhe mendërisht, Jonas po vendoset mbi të gjithë të tjerët në Komunitet. Gjatë gjithë jetës së tij, Jonas ka qenë gjithmonë ndryshe nga të tjerët. Ai vazhdimisht binte në sy sepse ishte i vetmi që kishte sy me ngjyrë të çelur. Në teori, sytë e dritës janë gjerësisht të njohur për të treguar më shumë një histori sesa sytë e errët. Në Ceremoninë e Dyshëve, Jonas fillimisht u anashkalua kur filloi përzgjedhja, duke e bërë atë të mendonte se ky ishte vetëm një gabim i vogël. Paniku i vogël lindi, pasi Pleqtë nuk janë të ndaluar kurrë të bëjnë një gabim, por shumë e pastruan atë si të tillë, shumë të frikësuar për të pyetur në të vërtetë për të. Sidoqoftë ai u hodh për një arsye, arsyeja ishte që pasi të gjithë të tjerët morën zgjedhjen e tyre, ai do të thirrej në podium për t'u thënë se do të nderohej tani dhe përgjithmonë. Plaku kishte deklaruar se Jonas ishte një person i veçantë, ai kishte “aftësinë për të parë përtej”. Thirrja e tij nga Plaku e bën atë të izoluar nga të tjerët. Kjo filloi një lloj hierarkie të pashprehur, por të njohur në Komunitet. Një moment Jonas ishte një nga qindra Të Dyshët që priste të caktohej një pozicion, dhe në momentin tjetër Jonas ishte një person i respektuar dhe i dallueshëm. Jonas nuk ishte i dashur për faktin se ai tani duhej të njihej, pasi pranimi do të thoshte se ai ngeci jashtë, duke provuar kështu pikën se si është në izolim të plotë kur bëhet fjalë për Marrësi i Kujtesës. I vetmi person që mund të shprehet dhe flasë me të vërtetë në këtë rrethanë, është Dhënësi. Përveç kësaj, komuniteti i Jonas gjithashtu nuk ka asnjë koncept të idesë së ngjyrës, dhimbjes dhe kafshëve. Kjo është shumë e parëndësishme për ta, asnjë shpirt në të gjithë Komunitetin nuk është në gjendje të perceptojë idenë e ndonjë prej këtyre temave. Kjo e bën atë të ndjehet sikur është i padrejtë si ndaj tij ashtu edhe ndaj qytetarëve në komunitetin e tij. Secilit i mungon aftësia që ka dhe në këto rrethana është arsyeja pse puna e tij si Marrësi i Kujtesës është një dënim. Tek Dhuruesi, Lowry thërret: “Ai vendosi një dorë në secilën nga shpatullat e tyre. Me gjithë qenien e tij ai u përpoq t’i jepte secilit prej tyre një pjesë të kujtesës: jo të britmës së torturuar të elefantit, por të qenies së elefantit ”(101). Këtu, Lowry demonstron ndjenjën e izolimit të Jonas në mënyrë shumë të konsiderueshme. Babai i Jonas është plotësisht injorant për atë që po bën, dhe motra e tij shqetësohet nga fakti që ai po e prek atë. Ajo nuk e dëshiron këtë lidhje fizike mes saj dhe Jonas. Kur Jonas i tregon asaj për ekzistencën e kaluar të elefantëve, ajo mendon se ai po tallet dhe thjesht e luan duke mos e besuar atë. Kjo e vë Jonas në një pozitë të ashpër sepse shprehja e ndjenjave ndaj familjes është diçka që shumë njerëz bëjnë për të nxjerrë të gjithë energjinë e keqe dhe për të hequr një peshë të madhe nga shpina. Sidoqoftë, pa pasur përvoja të ndara me askënd tjetër përveç Dhënësit, Jonas lihet i vetëm për t'u marrë me të gjitha rezultatet e dëmshme dhe të dobishme të dijes.

Kur dikush konsideron se protagonisti përjashtohet nga komuniteti i tij dhe se ai duhet të mbajë dhe mbajë të gjitha kujtimet dhe emocionet, është e qartë se pozicioni i tij është ai që e bën atë të sakrifikojë në mënyrën e tyre të jetës. Lowry dëshiron që lexuesi të marrë parasysh se çfarë ndodh kur njerëzit refuzojnë të pranojnë se ka vend për mundësi të shumta brenda një shoqërie. Ky refuzim për të parë se ka më shumë se një zgjedhje në çdo situatë të caktuar ngec në rritjen e tyre. Heqja e lirisë së zgjedhjes në emër të sigurisë nuk është kurrë një mënyrë e mirë për të jetuar. Mbi të gjitha, siç i shpjegon Profesor Dumbeldore Harrit në Dhomën e Sekreteve, “Janë zgjedhjet tona, Harry, që ne të tregojmë atë që jemi me të vërtetë, shumë më tepër sesa aftësitë tona. “

Argus and Io - Anglisht

From Eyes to Feathers: Discovering Transformation, Suffering and Meaning through Ovid’s Argus and Io Myth

Ovid’s version of the Argus and Io myth in the Metamorphoses is the perfect example for explaining how Romans attempted to transform suffering into meaning by connecting it with beauty in the natural world. Ovid employs transformation not just as a plot device for readers, but also as a psychological device for processing trauma. Through the transformation of Argus’s hundred eyes being carefully arranged into peacock feathers, Ovid turns violence and grief into the latter: understanding, art and beauty, all while symbolizing resilience and preservation through storytelling. The peacock's tail, derived from Argus’ hundred eyes, really shows what Dixon calls the “ambiguities of natural phenomena,” where a natural object simultaneously embodies violence, mourning, and extraordinary beauty.1 It situates Ovid’s writing within the psychological frameworks of trauma, as well as the “making of meaning”,1 which Ovid is known for excelling at, but also exists in both ancient philosophy and modern psychology. Argus’s death is transformed into the peacock’s beauty, which lives on and on, essentially eternally. Ovid uses Io’s parallel journey through trauma and fragmented identity as a physiological lens for understanding transformation as both a symptom, then recovery. This is where real, raw emotion, and human pain, rather than destroying identity, becomes a catalyst for reinvention and reinterpretation. All in all, Ovid demonstrates that transformation, even through suffering, is an act of preservation and renewal.

The story of Argus and Io in Book 1 of the Metamorphoses is a narrative about power, violation, and the attempt to be able to preserve identity through transformation. In the myth, Jupiter falls in love with Io, a river nymph and the daughter of Inachus. Juno, Jupiter’s wife, grows suspicious of an affair, and in turn Jupiter disguises Io as a cow in order to hide his infidelity. Juno then asks for the cow as a gift, and places Argus, a giant with a hundred eyes on his body, as its guardian. Ovid gracefully writes, “constiterat quocumque modo, spectabat ad Io, / ante oculos Io, quamvis aversus, habebat" (1.628-629), which I translated as “In whatever way he stood still, he looked toward Io. Even when turned away, he had Io before his eyes.” Argus’s sole purpose is to be a surveillant. His hundred eyes never sleep all at the same time, which makes escape for Io almost impossible. Under Argus’s surveillance, Io experiences complete suffering. In Ovid’s Latin, “frondibus arboreis et amara pascitur herba. / proque toro terrae non semper gramen habenti / incumbit infelix limosaque flumina potat” (1.632-632). I translated this as “She grazes tree leaves and bitter grass. And in place of a bed, she lies upon the earth not always having grass. Unhappy, she lies down and drinks the muddy rivers.” And, in one instance, when she attempts to stretch out her arms as a plea to Argus, she realizes she has no arms anymore. This is an allusion to the loss of identity that Io continues to face. In one of Ovid’s most keen details, when she tries to speak, “conatoque queri mugitu edidit ore / pertimuitque sonos propriaque exterrita voce est” (1.637-638). I translated this as, “And having tried to speak, she produced the mooing of a cow from her mouth, and she was terrified by the sounds and was frightened by her own voice.” This captures one of the most tragic moments in Io’s story. It is when she becomes aware of her speech loss. This loss of voice represents the complete fragmentation of identity. With this, goes her humanity as well. Her human consciousness is trapped within an animal body, and there is virtually nothing she can do about it.

In another particularly touching scene, Io encounters her father Inachus and sisters at the riverbank where she was once able to play by. They unfortunately do not recognize her. In distress, Io uses her hoof to trace letters in the dust, spelling out her name, and, therefore, revealing her transformation. Ovid captures this moment, “littera pro verbis, quam pes in pulvere duxit, / corporis indicium mutati triste peregit" (1.649-650). I translated this as, “A letter, traced in the sand by her hoof, stood in places of words. She therefore completed a mournful sign of her transformed body.” Her father’s response captures the contradiction of traumatic recognition: “me miserum! [...] tu non inventa reperta / luctus eras levior!" (1.651-655). I translated this as, “‘Oh, miserable me’! [...] you, not found, were a lighter grief than being found again.” Inachus is saying that the pain of losing Io was easier than seeing her like this. She is alive, but transformed into a cow. Finding someone is supposed to relieve grief, but Inachus’s discovery of his daughter only deepens it. This line articulates the real truth about trauma, that sometimes the acknowledgement of suffering is more painful than the uncertainty of it.

Jupiter, unable to bear Io’s continued and constant torment, sends Mercury to kill Argus. Mercury, who was disguised as a shepherd, is able to make Argus go to sleep by telling him stories and playing music. Then, as Ovid brilliantly writes, “nec mora, falcato nutantem vulnerat ense, / qua collo est confine caput, saxoque cruentum / deicit et maculat praeruptam sanguine rupem" (1.717-719). I translated this, “Without delay, he harms the snoozing one with his curved sword, where the head is in boundary with the neck, and throws the bloody head onto a rock, and stains the steep cliff with blood.” It is clear the violence is very graphic and brutal. However, what follows transforms this violence into something else entirely. Immediately after Argus’s death, Ovid writes one of the most significant lines of the story: "Excipit hos volucrisque suae Saturnia pennis / collocat et gemmis caudam stellantibus inplet" (1.722-723). I happily and carefully translated this as, “Juno takes these [eyes] up and in the feathers of her bird / arranges them and fills the tail with starry gems.” Juno places Argus’s eyes into the peacock’s tail almost like how a jeweler sets stones into pieces of jewelry. The verb collocat (places, or arranges) and inplet (fills) suggests a careful preservation as well as a reimagining. This is not random scattering. It is more of a deliberate arrangement. The eyes become gemmis…stellantibus (starry gems) transforming organs that were once used as a mechanism for surveillance into objects of beauty and purpose. The previous line, “Arge, iaces, quodque in tot lumina lumen habebas, / exstinctum est, centumque oculos nox occupat una" (1.720-721), which I translate as "Argus, you lie dead, and that light which you had in so many eyes / has been extinguished, and one night occupies a hundred eyes," emphasizes the totality of death before the transformation.

This transformation is extraordinary for what it accomplishes in a symbolic light. Argus, who existed solely as an instrument for surveillance and suffering, becomes immortalized as an object of beauty out in nature. The hundred eyes that once watched Io’s struggle and torment so vigilantly, are now the “starry jewels” that make the peacock one of nature’s most beautiful, and magnificent creatures. What makes this transformation psychologically significant is that it is able to make a basic human instinct tangible. This is the need to find meaning in suffering. The peacock’s tail serves as a permanent memorial to Argus. His identity is not erased by death. It is instead transformed, and made eternal. Yet, at the same time, the transformation also reinterpret’s Argus’s existence. He is no longer a mechanism for cruelty. Through Ovid’s clever syntax, Argus is now art, nature, beauty itself, and a symbol of Juno’s power.

To understand Ovid’s narrative strategy as purposeful rather than just decorative, we have to situate his work within the era of intellectual Augustan Rome and its traditions. Ancient civilizations possessed sophisticated frameworks for understanding how suffering is able to shape identity and consciousness. These are frameworks that, of course, predate, but mirror modern trauma theory.3 Greek philosophers, like Socrates and the Stoics, theorized very extensively about the relationship between experience, suffering and human flourishing. Socrates believed that ‘eudaimonia’, which is that act of happiness, wellbeing, and human flourishing, motivates all human action, and that virtue/knowledge lead to this state of wellbeing.4 For Socrates, life, even when painful, produces the wisdom necessary for human flourishing. These beliefs and ideas suggest that suffering itself, when understood and carried out properly, can become the catalyst for achieving this state of eudaimonia. Plato divided the soul into three parts. This was the desire, the courageous, and the reasonable, that must achieve harmony under reasonable guidance for a person to achieve wellbeing.4 When Io is transformed into a cow, she experiences the same kind of internal fragmentation of her identity that Plato described. Her human consciousness is trapped in the body of an animal, unable to achieve the level of consciousness that would restore her sense of self. She can think human thoughts, but there is no way for her to be able to express them. She can remember her identity and who she really is, but she cannot execute her identity.

Moreover, Plato understood the soul as mediating between the world of forms, which in this case would be the eternal and unchanging truth, and the world of sense, which is the physical and changing experience. The soul is able to generate perception, emotions, and experiences of pleasure and pain through the body.4 Io’s transformation makes this concept completely concrete. Io’s soul remains unchanged, as she knows who she is, while her body changes completely, as she cannot express who she really is. The Stoics, who were influential in Roman thought, emphasized finding one’s proper place in the natural order through acceptance and reinterpretation of suffering.4 This philosophy resonates with Ovid’s resolution. Argus’s suffering becomes immortalized. Thus, he is given permanent meaning through incorporation into nature itself. The peacock tail represents that Stoic acceptance transformed into art. Argus finds his permanent place, not as a victim, but as beauty.

Ovid, writing in a very intellectual culture full of saturation with all of these types of philosophical frameworks, would have been familiar with debates about how humans achieve flourishing through processing difficult, painful or traumatic experiences. His choice to transform Argus’ eyes into natural beauty, rather than just leaving them as just a tragedy on his gruesomely dead body, could suggest a possible connection between these philosophical traditions.

Io’s journey shows how transformation functions as both a symptom of trauma, and a pathway to recovery. Maggie Sawyer’s analysis in Io and Trauma in Ovid’s Metamorphoses interprets Io’s transformation as both symptoms and expression of trauma. Her suffering and voice loss go hand in hand with modern understandings of psychology and mental health. It mirrors the modern understanding of something called post traumatic dissociation.5 Following Io’s transformation into a cow, she experiences fear like no other. It is tied to the discomfort of being in the unfamiliar body of a cow. Then she attempts to speak and is only able to let out animal sounds, which is recorded by Ovid as, “pertimuitque sonos propriaque exterrita voce est" (1.638), I translated this as: “And she grew frightened by the sounds and was terrified by her own voice.” This specific detail is crucial. Io is alienated not just from her body, but also from her voice. The voice is the primary means of which identity is maintained. The loss of voice represents what trauma theory calls ‘narrative disruption’: the inability to tell someone's own story.5

Ovid emphasizes Io’s attempts to communicate regardless of this loss of her voice. She follows her family desperately, seeking for them to see and realize who she really is, beyond the skin of the cow. When verbal communication fails, she turns to physical communication. She uses her hoof to trace her name in the sand. This clever adaptation demonstrates what modern psychology calls resilience. It is the capacity to find alternative pathways when primary ones are blocked6. Io of course, cannot speak. However, she can write. Her consciousness is able to cleverly and quickly find an alternative in transforming her limitation into communication. Although, even after Jupiter ends Juno’s punishment, and restores Io back into her human and original form, the trauma persists. Ovid writes, “officio pedum nymphe contenta duorum / erigitur metuitque loqui, ne more iuvencae / mugiat, et timide verba intermissa retemptat" (1.744-746). My translation: “The nymph, satisfied with the use of two feet, rises and fears to speak, and in the manner of a cow, she timidly tries again the words she had left off.” The restoration of Io herself is physical, but the mental wound still lingers. Io has to relearn her own voice. This is perhaps Ovid’s most sophisticated psychological insight. This instills that transformation does not simply erase the trauma. The body itself might be restored, but the ‘self’ must be rebuilt.

John W Dixon’s exploration of The Ambiguities of Natural Phenomena provides a philosophical framework for understanding why Ovid’s transformation of Argus’s eyes into peacock feathers carries such a symbolic weight. Dixon argues that natural phenomena contain inherent ambiguities, the capacity to simultaneously embody contradictory meaning and emotions.1 As a natural object, the peacock's tail is very beautiful. It is rare to find such uniqueness in nature. It is admired across a plethora of different cultures and time periods largely for its iridescent colors, intricate pattern, and very dramatic display. Its origin in myth in Ovid’s narrative is rooted in violence and grief. Juno, by carefully arranging the ‘starry’ gems of a murdered guardian into the tail of an animal, literalizes the preservation of the dead through natural beauty. The peacock becomes more than just an animal with pretty feathers. It becomes a memorial, and symbol of warning, art, and most importantly, a reminder of resilience. By transforming instruments of surveillance and symbols of death into objects of natural magnificence, Ovid demonstrates how meaning can be extracted from suffering through creative reinterpretation. The peacock does not erase Argus’s death, it is instead able to preserve his existence while transforming its meaning. This is the essential mechanism of “meaning-making”, not denying the painful reality, but instead recontextualizing it within a larger framework that is able to make it bearable.1

Ancient civilizations were able to understand this principle very well. From Greek philosophical inquiry about the relationship between logos, divine reason, and the natural world,3 humans have always sought to read meaning into natural phenomena and to preserve painful experiences through their incorporation into the natural order. The Greeks saw stories within constellations, they explained season change through myths of abduction and return, they understood laurel trees, and flowers as metamorphosed humans whose stories continued in an altered form. Ovid inherits this tradition, but employs it with more psychological sharpness. His transformations are not punishments, but narrative strategies for processing what seems like the unprocessable to humans.

The Argus and Io myth is not isolated in the Metamorphoses, it is part of a more general, broader pattern. Ovid repeatedly employs transformation to demonstrate how identity persists through change, and how suffering can be preserved as beauty/meaning rather than just endured and lost, like it would be in many cases. Daphne's transformation into a laurel tree (Met 1.452-567) provides a parallel. Fleeing Apollo’s pursuit, Daphne prays to her father, a divine being. Ovid writes her prayer as, "fer, pater,...inquit 'opem! si flumina numen habetis, / qua nimium placui, mutando perde figuram!" (1.545-546). My translation: "’Bring help father!’ she said, ‘If the rivers have divine power, / by which I have satisfied too much, by changing destroy this form!’" Her wish is granted, and Ovid describes the transformation in sort of unique botanical terms: "mollia cinguntur tenui praecordia libro, / in frondem crines, in ramos bracchia crescunt, / pes modo tam velox pigris radicibus haeret" (1.549-551). I translate: "Her soft chest is surrounded by thin bark, / her hair grows into foliage, her arms into branches, / her foot now so swift is stuck fast in stagnant roots." Yet crucially, "remanet nitor unus in illa" (1.552)—"only her beauty remains in her.” Daphne’s transformation parallels Io’s in more ways than one. Both are pursued by gods. Both lose their human form and are disconnected with theit identity. Daphne’s transformation however, offers something that Io’s does not at first. That is, escape. The laurel tree cannot be taken advantage of. Her body is finally safe. Apollo immediately then claims the laurel as his sacred tree, adorning himself with the beautiful laurel branches. Yet, the transformation also preserves Daphne’s identity, "remnant nitor unus", her beauty remains. She becomes art, a symbol of victory. Her suffering is not erased. It is transformed into a cultural meaning that lasts for eternity. When Daphne turns into a laurel tree to escape Apollo, her father preserves her by transforming her body while her consciousness becomes a merge with nature itself. When Arachne becomes a spider after challenging Athena to a ‘weaving war’, her weaving skill, which she surrounded her identity so much on, continues in her new form of spinning cobwebs. Transformation in Ovid’s work preserves the core identity while changing expression, allowing traumatized individuals to continue existing in forms that aid their wounds. These patterns reveal Ovid’s consistent narrative strategy amongst more stories in the Metamorphoses than one. This strategy displaying that transformation serves as a mechanism for meaning-making, preserving identity and experience even through radical change of the body. Stoic philosophy taught that one’s true self, the rational soul, remained constant even as external circumstances changed it.4 Ovid brings this idea to life. His character’s bodies change, but their identities endure, whether that is being preserved through art, nature or skill.

Elizabeth Heimlick’s Trauma and Resilience Theory within Shakespeare’s Storytelling discusses resilience as the act of “bouncing forward into something both familiar and new”.6 This definition applies very well to Ovid's Metamorphoses, where physical change parallels psychological renewal. Argus’s transformation into art, with his eyes living on in nature, illustrates the timeless human drive to give permanence to pain through narrative storytelling. Modern trauma theory, particularly the concept of post-traumatic growth (PTG), is able to describe insight into the ancient world. PTG research demonstrates that trauma survivors often experience positive psychological changes. This includes greater appreciation for their life, stronger relationships, increased strength (personal), recognition of new possibilities and outcomes, and a deeper spiritual understanding.7 The key mechanism that facilitates PTG is meaning-making, the cognitive process of constructing explanatory frameworks that are able to integrate traumatic experiences into someone' s life narrative.7 This is precisely what Ovid’s transformation accomplishes narratively speaking. The peacock's tail makes meaning from Argus’s death. It does not erase his suffering or justify Juno’s cruelty, but it creates a framework in which that suffering has permanence, beauty, as well as significance. Just as modern trauma survivors are able to reframe suffering through creative expression like art, writing, etc,. Ovid’s characters transform suffering into meaning through metamorphosis. Helmick's theory turns trauma into a communal, overarching meaning that can be understood by universally anyone.6 This is exactly what Ovid’s myth does. The Argus and Io story becomes a teaching tale about how humans survive pain and suffering through transformation, through creativity, through the preservation of identity in altered forms. The peacock becomes a symbol accessible to everyone. You do not need to know the full myth inside and out to appreciate the bird’s beauty, yet knowing the myth adds layers upon layers of meaning to that beauty, which, in turn, adds a whole new dimension. Trauma survivors who reframe suffering through creativity and expression are engaging in the same “making of meaning” that Ovid displays. The veteran who processes combat trauma through painting, or the assault survivor who finds voice through poetry, or that grieving parent who establishes an organization in their child's name. These are all transforming suffering into beauty, meaning, art, legacy. They are, in essence, creating their own peacock tails. They are preserving painful experience by transforming it into something that both honors the past, and points toward continued existence.

The question of Ovid’s intentionality and whether he deliberately employed metamorphosis as a psychological mechanism for processing trauma becomes answerable when we consider his rhetorical situation. Ovid writes the Metamorphoses during the reign of Augustus Caesar, a period of intense political and social transformation. Rome had recently transitioned from being a republic into now an empire. Traditional Roman values that once upheld who they were, were being actively reformed, reimposed or replaced. Ovid himself would even eventually be exiled by Augustus. In this context, Ovid’s focus on transformation takes on political and psychological significance. His narratives consistently question divine authority and sympathize with victims of divine violence.8 Stephanie McCarter's 2022 translation specifically addresses how Ovid's narrative voice critiques the violence it depicts, often through subtle irony, focalization through victims' perspectives, and emphasis on the bodily and emotional suffering caused by divine power.8 Ovid’s narrative choices which focused on victims' experiences, emphasizing the emotional and physical details of transformation, displays a purposeful and deliberate strategy. He transforms these stories of divine cruelty into narratives of resilience. He invites readers to find meaning in suffering through his act of storytelling.

Works Cited

[1] Dixon, John W. "The Ambiguities of Natural Phenomena." The Christian Scholar, vol. 48, no. 3, 1965, pp.

183–97. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41177467.

[2] Ovid. Metamorphoses. Edited by Hugo Magnus. Gotha: Perthes and Besser, 1892. The Latin Library, http

s://www.thelatinlibrary.com/ovid/ovid.met1.shtml.

[3] Tiny Wonder. "A Brief History of Psychology: From Ancient Civilizations to Modern Science." Medium, 21

Feb. 2023, medium.com/@tinywonder/a-brief-history-of-psychology-from-ancient-civilizations-to-modern-scie

nce-19c259e9edee.

[4] Wilam, Allison. "Psychological Thoughts of Ancient Greece." Medium, 24 Feb. 2022, medium.com/@alliso

nwilam/psychological-thoughts-of-ancient-greece-68f87339a2db.

[5] Sawyer, Maggie. "Io and Trauma in Ovid's Metamorphoses: Rape and Transformation." Haverford

College, 2019.

[6] Helmick, Elizabeth. "Trauma and Resilience Theory within Shakespeare's Storytelling." Iowa State

University, 2022.

[7] Park, Crystal L., et al. "Meaning Making Following Trauma: A Self-Regulation Framework." In Trauma and

Self: A Theoretical and Clinical Perspective, edited by Andrew J. Moskowitz, et al., 2022.

[8] McCarter, Stephanie, translator. Metamorphoses. By Ovid, Penguin Classics, 2022.

[9] Curran, Leo. "Rape and Rape Victims in the Metamorphoses." Arethusa 11.1–2 (1978): 213–241.