VASSO NOULA

ARCHAEOLOGIST

SPECIAL ASSOCIATE OF MUNICIPALITY OF FARSALA

In the settlement Asprogeia of the local community Eretria of Farsala, on the eastern edge of Farsala, in an idyllic, bucolic landscape rises a monastic complex of the Ottoman period that belonged to the Order of Bektashi dervishes.

The Bektashi sect, from a dogmatic point of view, is located between the two major religious currents of Islam, Sunni and Shia. In fact, this mystical sect brings together key elements of all 3 religions that defined the life in the Balkans through the Ottoman period, namely Islam and Christianity, Judaism as well as shamanism. In this fact, namely that the Bektashi sect embraced many heterodox and heterogeneous data, lies the large degree of tolerance from the bektashi faithful towards the different religious beliefs of other people.

The Muslim monastery, formerly known with the name “Irene Tekes”, derived from the Turkish name of the village of Asprogeia “Irene”, was speculatively built on the ruins of a Byzantine monastery of the 10th century, dedicated to Saint George. It was well known throughout its lifetime, means from the late 15th century to 1973, when the 33rd and last Dad (abbot) of the monastery died.

The Den had (and still has) large land estate, which derived significant revenue and always gave it strength and power.

DESCRIPTION

The Den is built onto a small mountain balcony, from which one can stare at the whole plain of Farsala, without being noticed, a key element for anyone wanting to control the region and organize protection when danger appears.

The safety of the monastery was associated with the presence of a tall, strong wall enclosure, fortified with battlements and turrets, secret boxes, underground passages and hatches from which anyone could easily descend to the valley without being noticed.

At the Den’s entrance, before its main buildings, within a cluster of sycamores, a traditional stone fountain was towering. It belongs to the type of unilateral open tap with a shaped recess in its front, which is crowned by a large arch, that leads to two low pilasters. The fountain bares a simple plate made of cornice stones. In the lower portion of the arc’s drum there is the outlet of the water gutter, roughly carved, on top of which exists a small rectangular cabinet.

From this traditional fountain starts the last part of a gentle uphill dirt road that leads to a spacious paved square, enclosed by two building cores, south of the burial grounds of the monastery, and to the north of the communal courtyard. This paved area was once served as the monastery’s threshing floor.

A tall arched entrance led to the communal courtyard, which was protected by a three-pillar porch that does not exist anymore, despite subtle traces of its foundations. The entrance was blocked by a double wooden door, crowned with a conch baring battlements as well as and two turrets left and right.

Inbound to commune, visitors were located in an elongated, patio, defined by a series of buildings to E, W, N.

In the eastern part of the court, one can meet, in order:

• the abbey, a two-story stone building with arched doorways on the ground floor. In this structure the dervishes, who were about to become abbots, namely dads or sheikhs, needed to pass the required and necessary cleansing period that enabled them to take their rank,

• bakeries and kitchens, of which we preserve only ruins,

• warehouses, stables and granaries.

Hostels were lining on the western side of the courtyard, as well cells and also the bank. The major building of this axis is the monks’ retreat, which formerly housed the cells of the dervishes and the abbot. It is a massive, two-story building, with a multi-pillar loggia. Andreas Karkavitsas, who visited the monastery in 1892 and recorded his impressions in the newspaper “Estia”, states that “one vine ascends from the large gate ascends to the second floor, multi – graped and thick-shadowed, and two cypresses, rising in the midst of the yard immediately resemble the picture of a normal monks’ retreat. ”

Deep in the yard area and to the North stands the meidan, means the building that hosted the ceremonies held in the monastery. It is an elongated two-storey, fully stone-built construction, adorned with great relieving arches in its main aspect.

Το μεϊντάν

All these buildings situated in the northern communal precinct have been under numerous new arbitrary alterations, from what we know of modern Bektashi, who come here and think that it is their obligation to abusively intervene in the remains at will.

The cemetery of the monastery spreads through the southern burial enclosure. There exist two tourbes (mausoleums), surrounded by thirty-three graves. The western and older tourbes is a simple, one-room building, with maximum dimensions of 6 ? 7 ? 7,5 meters. The maximum height is calculated from the top of the dome, which is supported on four semi-funnels.

Concerning masonry, an irregular cloisonne system was used, where thin bricks surround stones of various sizes, which, according to some scholars, confirms that the building dates back to the 16th century.

In the southern and western side, walls are interrupted by arched, with a slightly pointed tip, openings. The north, main side of the mausoleum, is adorned with a small gallery, consisting of four columns crowned by arches, which form a three-part division in front of the building. The roof of the portico, and the wall of the tourbes entrance once bore very rich paintings with floral motifs, which are now covered by white color.

During the construction of the tourbes, architectural material of the Byzantine period was also contained in second use (columns and capitals).

The entrance door is surmounted by a simple-formed niche with stalactites.

Of similar shape and dimensions is the east tourbes as well, which also houses three tombs. The oldest grave of the two mausoleums has been dated to the 17th century and the newest one in 1869 (Egira year 1286).

Its stone construction consists of equally sized lime stones and it is covered with slate plates.

A newer concrete construction is the architectural element connecting the two mausoleums, through which the buildings communicate, while hosting two more graves.

All these graves belong to abbots (sheikhs) of the monastery.

The other grave monuments, surrounding the mausoleums, belong to dervishes, who were monks in the area and preserve several inscribed (in anaglyph Arabic script) tomb columns, and sometimes the head and legs of the dead, which extol their virtues. Other graves have a simpler form, bearing columns on top, with no inscriptions, having only the shape of tats, as a statement that the dead were priests. A third class of funerary monuments bear columns with pit-like hulls, into which Turkish worshipers were leaving copper coins as contributions. Some of the tombs belonged to faithful Bektashi citizens, who wanted to be buried in a shrine next to deeply faithful monks.

Like the buildings in the northern cenobiotic enclosure, so the buildings of the southern burial enclosure have been under new arbitrary interventions that dramatically altered the architectural and religious characteristics of the area.

SPECIAL NOTES

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE BEKTASHI ORDER

The Bektashi sect was one of the many mystical orders deployed within the bosoms of Islam, which through its evolutionary formation favored the creation of internal orders and mysticism (tasavvuf). The mystics were known by the general term “Dervishes” and created separate orders, each of which had its own ritual and their own places of worship.

From early on, Islam followed 2 axes of theological approach. From one point stood a formal, rigid, nerveless theology, which is expressed through an equally absolute, hard and rigorous religious law and from the other hand a different field of theological pursuits was created, which was expressed through mystical approaches that, in most cases , is based on the natural dire need of ordinary people to form a secular religion that truly aims at direct human contact with the knowledge of God.

Founder of the Bektashi sect is considered Hadji Bektas (Nissampour Turkmenistan 1245 / Hijra year 645 – Karachogiouk 1338 / Hijra year 738), the preaching of which had a great impact on the people of Asia Minor. He was reputed as a saint and his name was associated with a series of events, several of which date back to the realm of legend. However, he is considered the founder of the Order of the Janissaries, being the one that gave the order its and blessed it with the sleeve of his tunic.

THE BEKTASHI SECT PRINCIPLES

The Bektashi sect, from a dogmatic point of view, is located between the two major religious currents of Islam, Sunni and Shia. In fact, this mystical sect brings together two key elements that defined the religious life in the Balkans through the Ottoman period, namely Islam and Christianity as well as shamanism, the ancient pre-islamic turkish religion and ancient Greek philosophy. In this fact, namely that the Bektashi sect embraced many heterodox and heterogeneous data, lies the large degree of tolerance from the bektashi faithful towards the different religious beliefs of other people.

In line with Christianity, the Bektashi believe in the Holy Trinity, which for them is composed by God, Muhammad and Ali, and in accordance with their faith those three instances are an indivisible unity. They also respect and believe in the twelve Imams, in correspondence with the twelve apostles of Christianity.

In addition, they believe in the Holy quintet, consisting of Muhammad, Fatme, Ali, Hassan and the Hussein. They also believe in reincarnation, while a central position in their teaching hold aversion (temperra) and friendship (tevella).

The basic principles of Bektashi, which should be the guide of the lives of its believers are: obedience, humility, confidence, patience, temperance and hilarity.

The Bektashi do not seem to have any public religious practice. Their mystical ceremonies, including the ritual of worship, are: the Ikrar ceremony(an introductory confession of faith ceremony for the neophyte), the Cem ceremony (a Bacchanalian-like ceremony in which, opposingly to the principles of Mohammedanism, was accompanied with dance and wine consumption), the cassock-wearing ceremony and the ceremony Nevrouz.

In the administrative hierarchy of the Bektashi seven ranks are distinguished, divided into three classes. The first introductory class includes: a) the Asiki, b)the mouchib – suitors, c) the friends and d) the dervishes. In the next class we meet the Baba (the abbots of local dens) and Dervis i Mountchourant. On the higher rank are the Caliph, as heads of regional dens, the Dede – Dads, who are heads of the seats and finally the Çelebi, who were leaders of married Bektashi and descendants of Bektas himself.

Finally, in terms of formal attire, Bektashi upper class (from Dads and and higher), consisted of the twelve-crease matrix, a mantle, two knives, a bag bearing from the neck, the pectoral cross, the flag and a lamp.

The apparent adoption of many elements of Christianity in the theological and ritual organization of the Bektashi, led many to believe that this religion did not stem from spiritual and theological pursuits, but that it was a deliberate choice aimed at the massive Islamization of Christians.

For five consecutive centuries the Bektashi order followed an upward trend with a steadily growing power in the Ottoman society and religious organization. When the battalion and its associated Janissaries corps reached the pinnacle of glory and power in the early 19th century, was considered by the Sultan Mahmud II Sultan threatening to the regime, and as such was abolished in 1826. The total demise of the Bektashi Order of Dervishes came with the decree of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1925, which, under the guidance of Kemal Ataturk, ordered the destruction of all existing dens in Turkish territory and the prosecution of mystical monastic orders acting on it, without any exceptions.

IRENE TEKES (DEN) – HISTORICAL SURVEY

The monasteries of Muslim mystics were called “tekes” (dens) and were often large institutions in the countryside, structured and organized within enclosures in line with Christian monasteries. One of the most prosperous Bektashi dens in Greece, active until 1970, was located in the village Asprogeia Farsalon, in an idyllic, bucolic landscape.

The Muslim monastery, formerly known with the name “Irene Tekes”, derived from the Turkish name of the village of Asprogeia “Irene” was well known throughout its lifetime, ie from the late 15th century to 1973, when the 33rd and last Dad (abbot) of the monastery died.

As often happened with these dens, the Irene Tekes was speculatively built on the ruins of a Byzantine monastery of the 10th century, dedicated to Saint George. Both its reconstruction and operation were modeled in accordance to required standards found in many Christian monasteries. Its founder allegedly was the turkish fanatic Bektashi – dervish Ntourbalis, who came from Iconium in Asia Minor and relcoates to Asprogeia in 1492/911 Hijra year. The official Turkish authorities in Thessaly granted dervish Ntourbalis permission to establish a den in Irene, in recognition of the invaluable military service he offered them in the military field, something that contributed to the complete conquest of Thessaly, the subjugation of the Christian population and its potential Islamization. Over the next centuries, Irene’s den was strengthened with the estates of villages Irene (Asprogeia Farsalon) and Arntouan (Eleftherohori Magnesias), an area sprung across thirty-two thousand (32,000) acres, actions which made him financially strong.

According to some studies, Ntourbalis Sultan was a mythical figure and the den owes its name to an alteration of the Turkish word Tourbes or Ntoulbes, meaning “tomb”. It was a name often given to called mausoleums and mosques, so that perhaps was the name for the entire monastery, ie Ntoulbali Tekes = Den of the Tombs or Den of the entombed.

The dens operated as outposts, supply centers and association links with the regional administrative power,. They were also mainly propaganda sites to promote Turkish language, battering rams for the spread of Mohammedanism and Islamization of Christian populations.

A turning point in the history of Irene Tekes were the events in the middle of the 18th century. At that point there was a noticeable change in the geographic origin and ethnic origin of Dads (abbots) of pious foundations. While until then, despite a few exceptions, the abbots were of Turkish origin, suddenly, in the vast majority, the abbots began originating from Albania. The decisive event that led to the turn of events, must be sought in the actions of Ali Pasha Tepelenli. Ali Pasha, a known Bektashi himself, in that period, appends Thessaly in his territorial influcence and for obviously political reasons he passes the control of the den to Albanians.

The total and irrevocable Albanian conversion of the den was made possible due to the law passed by the Turkish Grand National Assembly in 1925 about the destruction of dens. It was then that the supreme authority, which supervises the den of Asprogeia, leaves Turkey and finds hospitable refuge in Albania.

TODAY

Today, although it is a listed monument, the situation of this deserted and ruined monastery, where all its buildings are on a small or advanced degree of collapse, requires immediate and effective intervention. An area laden with historical memory, intercultural and inter-religious significance, should be preserved and restored, and it would be interesting to house an international center for the study of people and religions of the Balkans over the last five centuries. In this direction, the Municipality of Farsala gathers its forces.

ΕΝΔΕΙΚΤΙΚΗ BIBLIOGRAPGY

α) Βαϊρακλιώτης Λάκης, Οι Τεκέδες των Μπεκτασήδων στα Φάρσαλα, Θεσσαλικό Ημερολόγιο, τόμος 25 (1994)

β) Γιαννόπουλος Νικόλαος, Μεγάλη Βυζαντινή Μονή εν τω τεκέ των Φαρσάλων, Επετηρίς Εταιρείας βυζαντινών Σπουδών, τόμος 14 (1938)

γ) Καρατόλιας Αθανάσιος, Τα Φάρσαλα από αρχαιοτάτων χρόνων μέχρι σήμερα, Λάρισα 2012

δ) Καρκαβίτσας Ανδρέας, Ο Τεκές των Μπεκτασήδων, Άπαντα Καρκαβίτσα, Αθήνα 1973

ε) Τσιακούμης Παναγιώτης, Ο Τεκές των Μπεκτασήδων στο Ιρενί Φαρσάλων, Λάρισα 2000, εκδόσεις έλλα

στ) Χούλια Σουζάνα, Τεκές Ντουρμπαλή Σουλτάν, Η Οθωμανική αρχιτεκτονική στην Ελλάδα, ΥΠΠΟ, Αθήνα 2012

Ndajeni këtë me të tjerët:

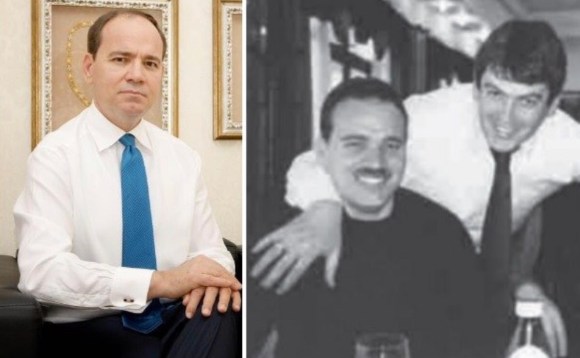

Ka qenë vetëm një moment pakujdesie që ambasadori i Bashkimit Europian në Tiranë, Luigi Soreca ka hapur telefonin gjatë një ceremonie me rastin e publikimit të Raportit të Progresit, por pa dashje ka zbuluar edhe një pjesë nga bisedat e tij me kryeministrin Edi Rama. Ekrani i telefonit të diplomatit italian është i mbushur me mesazhe dhe sinjalizime, por ai zgjedh të shohë çfarë shkruan në WhatsApp kreu i qeverisë shqiptare.

Ka qenë vetëm një moment pakujdesie që ambasadori i Bashkimit Europian në Tiranë, Luigi Soreca ka hapur telefonin gjatë një ceremonie me rastin e publikimit të Raportit të Progresit, por pa dashje ka zbuluar edhe një pjesë nga bisedat e tij me kryeministrin Edi Rama. Ekrani i telefonit të diplomatit italian është i mbushur me mesazhe dhe sinjalizime, por ai zgjedh të shohë çfarë shkruan në WhatsApp kreu i qeverisë shqiptare.

Nga Gazmend Kapllani/

Nga Gazmend Kapllani/

Pas mbarimit të punës voluminoze për hartimin e gjashtë letrave drejtuar Bashës, Kryeministri i vendit ka hartuar një tjetër strategji kombëtare, që do t’i habisë të gjithë shqiptarët. Së bashku, me stafin e tij të PR në kryeministri, ai do lançojë fushatën e grumbullimit të fondeve në shumën prej 140 milion eurove, për pagesën, që duhet të bëjë pas humbjes së gjyqit të Arbitrazhit në Washington.

Pas mbarimit të punës voluminoze për hartimin e gjashtë letrave drejtuar Bashës, Kryeministri i vendit ka hartuar një tjetër strategji kombëtare, që do t’i habisë të gjithë shqiptarët. Së bashku, me stafin e tij të PR në kryeministri, ai do lançojë fushatën e grumbullimit të fondeve në shumën prej 140 milion eurove, për pagesën, që duhet të bëjë pas humbjes së gjyqit të Arbitrazhit në Washington.

E kush tjeter do ta meritonte drejtimin e Akademis se shkencave shqiptare, vec shkencetarit Skender Gjinushi.

E kush tjeter do ta meritonte drejtimin e Akademis se shkencave shqiptare, vec shkencetarit Skender Gjinushi. Ylli Manjani, ish-ministri i Drejtësisë i ka bërë një thirrje ish-shefit të tij, kryeministrit Edi Rama: Shko në zgjedhje! Manjani ka shkruar në Fb: “ “Asnjë shans të ndryshoni qeverinë pa zgjedhje” – kumton Kryeministri në letrën e tretë të mllefit kundër opozitës.

Ylli Manjani, ish-ministri i Drejtësisë i ka bërë një thirrje ish-shefit të tij, kryeministrit Edi Rama: Shko në zgjedhje! Manjani ka shkruar në Fb: “ “Asnjë shans të ndryshoni qeverinë pa zgjedhje” – kumton Kryeministri në letrën e tretë të mllefit kundër opozitës.

O Minister i Brendshem! O misherim i paaftesise dhe dallkaukllekut!

O Minister i Brendshem! O misherim i paaftesise dhe dallkaukllekut!

Përtej kësaj bindjeje të brendshme që Hajredin Meçaj e shfaqte kurdo kur binte fjala për historinë e atyre viteve të stuhishme, ish-truproja i Enverit, në kujtimet e tij, tregon raste konkrete ku fryma bajraktare e drejtuesve të veçantë të Lëvizjes Antifashiste Nacionalçlirimtare ka shkaktuar pasoja të rënda, madje edhe me jetë njerëzish. Shpërfillës deri diku ndaj qasjes së kohës, ai guxon të rrëfejë një ngjarje tronditëse të padëgjuar më parë, që bëhet akoma rrëqethëse nga fakti se nuk ka ndodhur në ndonjë repart të skajshëm, por brenda në Shtabin e Përgjithshëm të Luftës.

Përtej kësaj bindjeje të brendshme që Hajredin Meçaj e shfaqte kurdo kur binte fjala për historinë e atyre viteve të stuhishme, ish-truproja i Enverit, në kujtimet e tij, tregon raste konkrete ku fryma bajraktare e drejtuesve të veçantë të Lëvizjes Antifashiste Nacionalçlirimtare ka shkaktuar pasoja të rënda, madje edhe me jetë njerëzish. Shpërfillës deri diku ndaj qasjes së kohës, ai guxon të rrëfejë një ngjarje tronditëse të padëgjuar më parë, që bëhet akoma rrëqethëse nga fakti se nuk ka ndodhur në ndonjë repart të skajshëm, por brenda në Shtabin e Përgjithshëm të Luftës.

Nga Kastriot Dervishi

Nga Kastriot Dervishi

Rama po kontrollon në mënyrë absolute parlamentin.

Rama po kontrollon në mënyrë absolute parlamentin.

Pansllavizmit dhe Rusisë putiniane i nevojitet zjarri dikund në Ballkan.

Pansllavizmit dhe Rusisë putiniane i nevojitet zjarri dikund në Ballkan. Krasniqi thekson se “Pansllavizmit dhe Rusisë putiniane i nevojitet zjarri dikund në Ballkan.”

Krasniqi thekson se “Pansllavizmit dhe Rusisë putiniane i nevojitet zjarri dikund në Ballkan.”

Vuçiç gjithashtu i përgënjshtroi njoftimet e Thaçit, se, sipas tij, “Hashim Thaçi i ka kërkuar Serbisë në të gjitha takimet që ata kanë patur që të njohë Kosovën së bashku me tri komunat e jugut të Serbisë.” “Më lejoni t’jua them tani, mos e çoni nëpër mend”, u tha Vuçiç gazetarëve.

Vuçiç gjithashtu i përgënjshtroi njoftimet e Thaçit, se, sipas tij, “Hashim Thaçi i ka kërkuar Serbisë në të gjitha takimet që ata kanë patur që të njohë Kosovën së bashku me tri komunat e jugut të Serbisë.” “Më lejoni t’jua them tani, mos e çoni nëpër mend”, u tha Vuçiç gazetarëve. Hashimi mori pozat e një viktime të sulmeve të padrejta që janë ndërmarrë prej tij gjatë kohëve të fundit për atë që ai e mohoi të ketë një plan për nadrje të Kosovës.

Hashimi mori pozat e një viktime të sulmeve të padrejta që janë ndërmarrë prej tij gjatë kohëve të fundit për atë që ai e mohoi të ketë një plan për nadrje të Kosovës.